Background

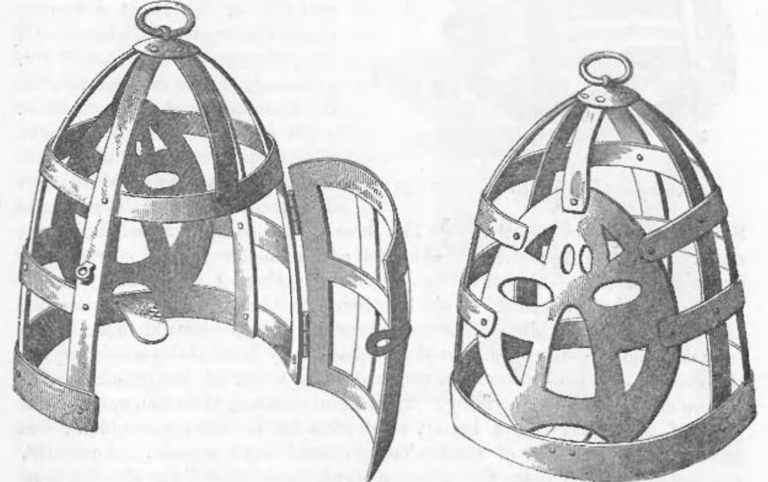

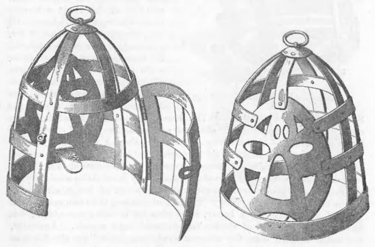

Described contemporaneously as an ‘engine of torture’, this ridiculous crown of iron was locked around a scold’s head, barbed with a bit to muzzle her insolent gossiping, which tore at her mouth as she was yanked around town. Its visible brutality provides us with a clear window into how technology is employed to injuriously silence resistance. Dubravka Ugrešić compiles a list of the victims eligible to wear it from across languages and cultures:

“chatterboxes, gossips, busybodies, yentas, yakety yaks, nags, harpies, shrews, vixens, quibblers, spitfires, hags, magpies, blabbermouths, loudmouths, prattlers, tattletales, hawkers, fussbudgets, floozies...”

In the mask, we see not just an artifact in a vacuum, but a succinct manifestation of cruel technological networks designed to silence identities as a means to dominate and ridicule the margins of society.

The Iron Gag

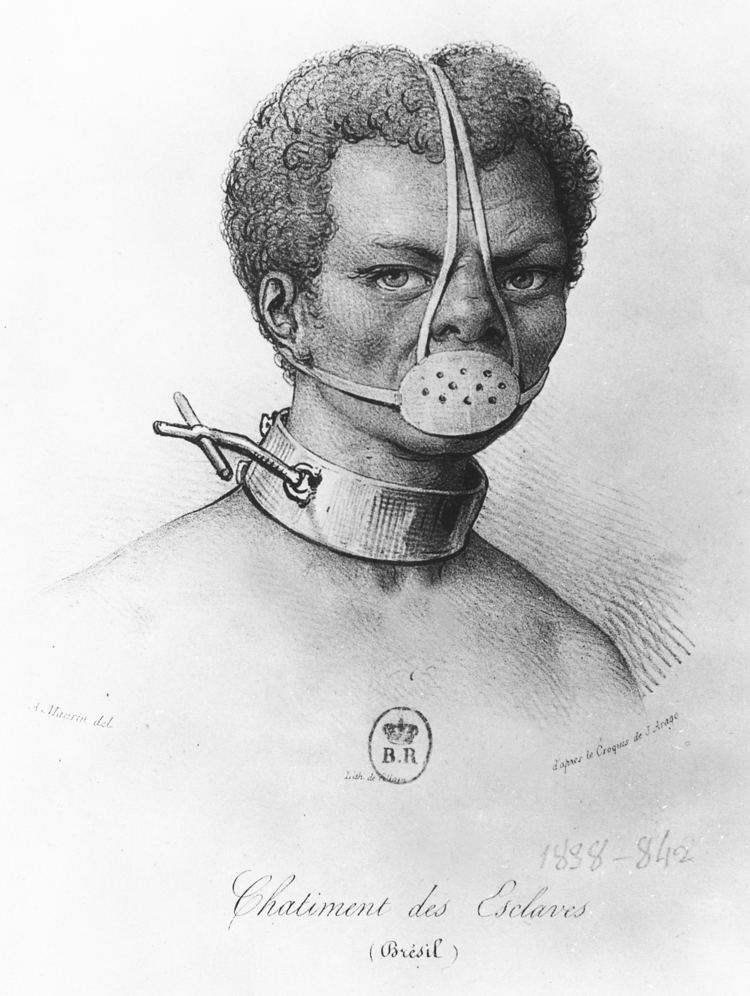

The Scold’s Bridle was used in Europe between 1546 and (at least) 1856 to torture and publicly humiliate combative/assertive women, but this technology took on different roles in the Americas. Instead of the brief ritualistic shaming of the Scold’s Bridle, the identical iron gag was used to silence and control enslaved people for much longer periods. In some cases, when enslavers did not provide enough nutrition, the iron gag took on a medical role to prevent ‘cachexia africana’, a condition invented by white physicians to describe why enslaved people ate dirt as a last-ditch effort to combat starvation. This also served a dual purpose of preventing ‘drapetomania’ (running away), as the gag could only be unlocked with a key at the enslaver’s permission.

Despite these technologies being nearly identical, they were used in completely different ways depending on the social context in which they were embedded. Even though these masks fell out of use, the silence that was essential to preserving the same dominant power structures lives on - it is no coincidence that the voices of women and people of color are still stifled all these centuries later. By telling the stories of these victims, the power structures that depended on their silencing are uprooted for all to see and hear.

Prototyping

Given that the mask’s function was to silence the wearer, the best way to bring attention to these histories is by amplifying the wearer’s voice. Early prototypes attempted to incorporate a nose-blown death whistle. While building the first metal prototypes, the rigidity of the cage had ideal acoustic properties that meant it could be resonated using a surface exciter speaker.

Electroacoustic Feedback

Building off of the steel frame’s acoustic properties, a kalimba in the shape of a mustache was made from electrical equipment. A contact microphone inserted under steel lips (doubling as a vocal microphone) allowed for a closed feedback loop to occur. A patch in Pure Data was used to control this feedback, with randomized gain and secondary feedback banks to induce a wide range of sounds.

By attaching a shaving razor to the surface exciter and running it over the kalimba tines, the heavily gendered act of shaving becomes a ritualistic performance depicting how technology is implicated in gender dysphoria. This video, which demonstrates this effect, gained 2.9 million views on TikTok.

Future Work

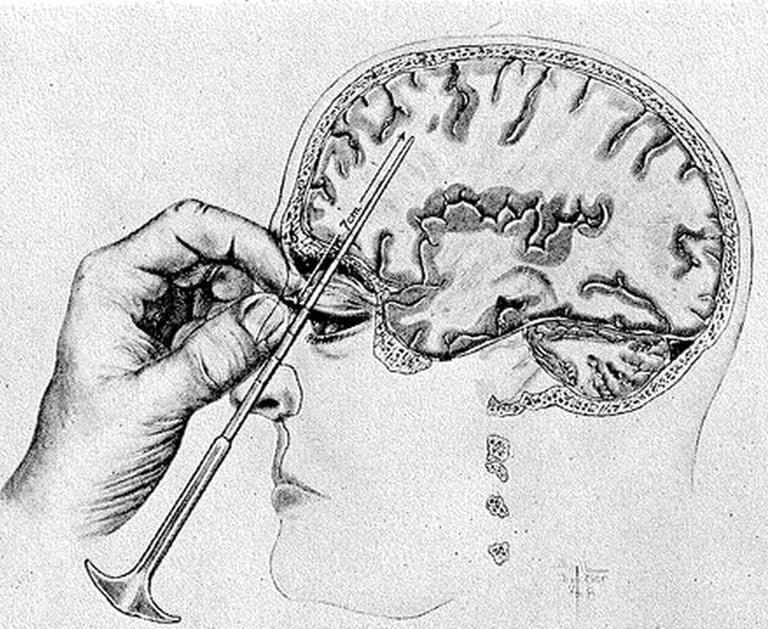

As the Scold’s Bridle became obsolete, other technologies replaced it. Incorporating instrumental elements such as an extendable tine along the nose can be used to performatively replicate lobotomies, which also disproportionately victimized people of color, women, and queer people.

Videos depicting my Scold’s Bridle have received over 2000 comments on TikTok, many of which make connections to queerness, lobotomies, autism, and other media like the Saw movies. Sonifying the community engagement with the project through the use of popular text-to-speech voices can illuminate who holds stakes in this technology today, and how the internet both facilitates and hinders discourse.